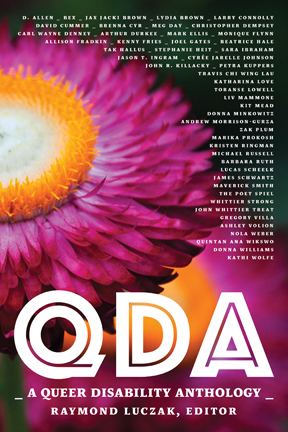

Sometimes, a book drops in your lap like a miracle you didn’t even know you needed. That’s what happened with QDA: A Queer Disability Anthology edited by Raymond Luczak and published by Squares & Rebels Press. I never thought speaking up about disability exclusion at AWP would connect me with a community of writers with disabilities, but that is what happened–starting with an email from Luczak inviting me to review the QDA anthology. I jumped at the chance because I didn’t know there were disability anthologies out there. I actually said out loud, “WHAT? This exists?”

I also saw it as an opportunity to learn more about the intersection of sexuality and disability, something I knew cut much deeper than I understood as a straight, white woman with disabilities. In this regard, QDA blew my mind.

Many of the writers in QDA live in a perpetual state of marginalization, even among people who share their sexual orientation or disability, as in Missing What You Never Had: Autistic and Queer by Kit Mead, in which Mead explores being an “invisible queer person.” Mead’s queer sexual orientation and agender identity have come under fire because people with autism aren’t “supposed” to be either. At the same time, autism creates social barriers to queer spaces, such as the LGBT Pride parade. “[W]hen I tell people I’m autistic and queer,” Mead writes, “Will I be welcome in their spaces? Especially when I ask them to turn down the volume?”

Compartmentalization becomes survival strategy, perhaps best exemplified by Nola Weber’s essay, The Worst, Most Faithful Friend, about living with vaginismus and vestibulodynia, an “overgrowth of highly sensitive nerve endings” in her vulva that sparks a “sharply prohibitive burn” at any attempt at penetration:

My physical limitation thus assured I could never excel at being straight, yet my unusual condition seemed just too suspicious not to question the coincidence that I was, in fact, quite queer … Perhaps this is why, in casual conversation, my vulvar pain and sexuality are not often co-disclosed: a lesbian who can’t be penetrated lacks the sympathy granted to her heterosexual counterpart, and a woman who has never felt straight sex might not ‘really’ be a lesbian.

It’s the ultimate double bind: her sexuality is questioned because of her disability, but her disability isn’t taken seriously because of her sexuality. For one part of herself to be taken seriously, the other must remain concealed.

If vulvar pain seems like a surprising condition to include in a volume about disability, that’s because the anthology embraces an expansive definition, something Weber feels unsure applies to her. “Applied to my own body,” she writes, “the term feels hyperbolic, dishonest, like a standard experience not quite mine to claim, and one true only in the most literal sense–in the sense of not being able.”

It’s one of the things that makes QDA so great. It does not exclude bodies the way so many cultural spaces do. Nor does it shy away from direct challenges on the dominant imagery of disability.

Mention disability, and the image that pops into many people’s minds is the universal access symbol of a person in a wheelchair:

For some of the writers in QDA, that’s a source of frustration. In Disability Made Me Do It or Modeling for the Cause, Kenny Fries writes of being invited to model for a guide to gay sex, and when he is asked how to portray a disabled man having sex he says, “Don’t use a wheelchair to signify the man is disabled.” Fries agrees to model, but his worst fears come true when the artist suggests “amputating” one of his legs out of the drawing or adding a wheelchair so his disability will “read” better.

Later, Fries imagines the hot spray of a shower dissolving his limbs until he transforms into a male Venus de Milo, who “despite her scarred face and severed left foot, despite having the big toe cut off her right foot, and missing left nipple, not being real, is considered one of the most beautiful figures in the world.”

On the other hand, in The Politics of Pashing, Jax Jacki Brown revels in what she calls the “crip privilege” of “pashing” (French kissing) her girlfriend in public, as onlookers struggle to reconcile her public display of affection with her wheelchair. “Queer sexuality and disability places me so far outside the realms of everyday that it renders people silent … leaving me able to pash my lover in public without a nasty comment.” For her, it’s almost a super power.

That said, QDA is not inspiration porn. You know the memes: the little boy in the wheelchair playing basketball with the tagline, “Your excuse is invalid”; the woman with a prosthetic leg running a marathon, demanding, “What’s your excuse again?” Luczak gives inspiration porn the smackdown in a powerful introduction that weaves together his personal experiences as someone who is deaf with the larger cultural questions and themes in the anthology.

Neither is QDA about overcoming disability. In fact, as Luczak’s own story unfolds in the introduction and later in his poetry, a profound need to embrace his deafness emerges. Luczak, who longed so badly to learn sign language that he made off with his big brother’s Boy Scout Handbook for illicit self-lessons in the manual alphabet, imagines a world where genetic engineering has “fixed” deafness and deaf people will “walk forever wounded,/searching for our phantom hands/never quite there but never quiet.” The implications are profound: even when “cured,” deafness is not cured, because it is more than a disability.

But also, in spite of all the inspiration porn, able people seem to need disability:

“In time you hearing people, too,

will long for us savages,

communicating in grunts and gestures,

if only to remind you that you are God.

It is in your nature to seek imperfections,

rout them out. After all,

you must have something to do.”

Perhaps because of how QDA found its way into my mailbox, I couldn’t help but howl (in the best way) at How Not to Plan Disability Conferences by Lydia Brown. #1: “Form a planning committee without any actually disabled people on it.” (Quick, somebody dial A-W-P.)

And I cannot bow out without a mention of Liv Mammone’s should-be-required-reading-for-every-MFA-program piece, Advice to the Able-Bodied Poet Entering a Disability Poetics Workshop. Oh, hallelujah! Hard to pick a favorite from it, but “Don’t ask if able-bodied people have really said and did jaw-dropping things in my poems. It’s hard to invent ignorance” is a strong contender.

Ultimately, QDA is an appeal to the common humanity that binds us all — or should bind us all. We all want love. We all want to belong. As Luczak writes so beautifully in the introduction, “Here we are, coming out not only as queer and disabled but also as human beings in these pages … Stop keeping us at arm’s length. Interact with us. Make friends. Maybe you’ll fall in love. (Hey, you never know!).”

Really interesting. Do you think defined spaces for certain groups of people (as you mentioned here LGBT) can be a hindrance?

Good question! I am not sure. I have to think about this question some more. (Sorry for the delay approving your comment. I somehow missed it! My apologies.)