Yesterday, I saw Lisa Oppenheim; Spine at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Denver. I was not expecting it, and I haven’t recovered from it.

When I rolled my rollator into the gallery, unaware what the exhibit was about, I was confronted with life-sized photographs of early 20th century textile workers, backs turned to the camera, their spines curved from repetitive movements and poor ergonomics (Fig. 1).

Spines like mine.

Well, sort of like mine. Those spines bent from hard labor; mine bent from a spinal cord condition and genetic connective tissue disorder.

The last time I was in this gallery, the staff seemed nervous about my body–ataxic, unsteady gait, pushing a wheeled walker–getting too close to the art. They shot me worried glances as I approached the exhibits, as if I might crash into them.

When I saw the Spine photographs, I could not breathe. I had to sit down. I watched as people without mobility aids, with no curves in their spines, paused in front of the photos, and said, “Can you imagine?”

Oppenheim did not take these photographs; she repurposed images she found in the Library of Congress, shot by investigative photographer Lewis Hine during the early 20th century for the National Child Labor Committee. For this exhibit, the photos are all young feminine-coded workers, all with scoliosis. These images alternate with photos developed from color negatives of fabric remnants of the same era, visually connecting the women’s spines to the textiles they produced while playing with digital & textile mediums, as well as means of production.

According to the MCA Denver exhibition catalog, Oppenheim “disrupts Hine’s technical, documentary approach by making us aware of how very human these young women are. Oppenheim opens up Hine’s imagery to see beyond the trauma of industrial production; she invites us to recognize their humanity through an appeal to sensuality.”

I have found no information that Lisa Oppenheim identifies as disabled or has the particular spinal issues depicted in Hine’s photography, which for me, is problematic: it is not her humanity to reclaim. Abled people are always using disabled bodies to claim something about humanity, and apparently, they can get on gallery walls without even taking their own images. This is not usually the case for disabled artists who use our bodies in our work (more on that later).

It is strange that Oppenheim did not see the humanity in the originals: Hine intended, in fact, to convey humanity. He took these photos with an eye toward social justice. His work contributed to the passage of child labor laws.

For her part, Oppenheim bisects the images with a white, straight line next to the curved back.

The original by Lewis Hine vs. the appropriated work by Lisa Oppenheim (Fig. 2):

MOCA Cleveland describes the intent of the white line as “creating an intimacy between the subject and the photograph itself.”

Here, the subject is a feminine-coded young person seated in a work chair, with a curve in the spine causing the left shoulder to droop. Oppenheim’s white line emphasizes this curve, almost like a yardstick or ruler held against the back. It does not feel intimate, but rather, an attempt by Oppenheim to leave a trace of herself, a physical marker of how she viewed these bodies. They suggest a yardstick for “normality” and a “healthy backbone,” while simultaneously reducing the women’s backs to an aesthetic. It is a kind of abstraction, and to my eye, a representation of the abled gaze–ultimately, dehumanizing rather than humanizing.

In the gallery, I watched how people interacted with the exhibit, and there was a disconnect between the fabric prints & remnants and the photographs. Nobody seemed to connect them, aesthetically, metaphorically, or otherwise.

In Jacquard Weave (Fig. 3), the metaphor becomes literal, the straight lines of the fabric threads reminiscent of the bisecting line in the photographs. Here, it is not imposed, but part of the process of creation–much like the workers’ bodies were created (or exacerbated) by the factory machines.

It raises interesting questions about artistic production and the body, particularly since many arts can be disabling. Dance leaves lasting injury. Painting exposes artists to toxic fumes and carcinogens. Many performance artists injure themselves for their art, Chris Burden perhaps the most extreme example. For me, this also raises questions about the way bodies get used as metaphors.

Oppenheim seems to be comparing her privileged artistic process to that of the factory workers, which might be true in some respects–intense physicality, poor ergonomics–but is wildly untrue in others. The Jacquard loom, she explained to Vice, is similar to photography: “a binary logic, like the presence or absence of light, ones and zeros, or in the case of the Jacquard loom like a punch card that’s empty or full. The relationship between these technologies is there from their beginnings” (Gat). But this reduces factory production and the trauma associated with it to mere aesthetic.

Few people in the gallery yesterday even stopped to read the descriptions or look at the fabric prints. The shock value of the curved backs had already overwhelmed them. As I watched them stand before these images and pity the bodies depicted in them, I started to see their backs as straight lines, too, imposed over the image: abled gazes and abled bodies eclipsing the subjects on the gallery wall.

As a disabled artist who does have these particular “deformities,” I can tell you that my body is not welcome in the museum space. Prime example: my Parallel Stress series.

This photo documents a performance where a sidewalk in my local community ended, thus ending my access. I purposefully struck an excruciating pose that challenges my balance, hurts my spine, hyperextends my knee, and places me in danger of injury. My cane, held in the wrong hand with the forward foot, does little to aid my balance (Fig. 4).

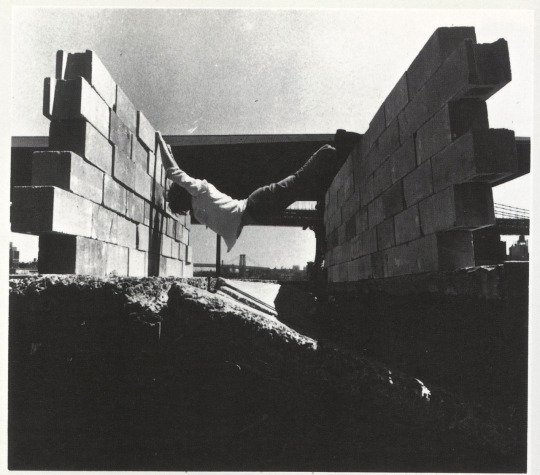

I created it conversation with Parallel Stress by Dennis Oppenheim (Fig. 5):

Dennis Oppenheim also held a painful pose as a way to explore the relationship of the body to the built environment.

On a whim one day, I applied an Instagram Prisma filter to Parallel Stress and the response was disturbing: able-bodied people unanimously declared it much more worthy of gallery space–indeed, much more “artistic” (Fig. 6).

One abled person wrote: This image is absolutely stunning. The original was. But this one is something else entirely.

Something else entirely indeed. Something other than dis art. Something other than the performance piece I was intentionally referencing and questioning. Something other than my body.

Even when I confronted them with the intention of the work, its grounding in performance art, and the problematic nature of erasing a disabled body to suit the abled gaze, they balked. They didn’t think they should be expected to take my art–or my body–for what it is unless I made it palatable for them.

Which is another way of saying: the Prisma filter functioned as a metaphorical cure. Notice how my walking cane disappears into the patterns of the Prisma version, the crook of the handle barely visible. Notice how the built landscape–the very urban planning I was critiquing–dissolves into abstract shapes resembling mountains in the background and the sea at my feet. The space I am straddling is no longer something for which abled people bear any responsibility. It’s nature. The abled gaze indeed tends to see the environment built for it as natural.

Even my hypermobile knee–hyperextended because of my Ehlers Danlos Syndrome–in the original picture gets erased by Prisma. The Prisma filter has rendered me abled.

Another abled person wrote of the Prisma filtered image, “Now THIS ONE belongs on a gallery wall.”

The problem is, the original image has hung on gallery walls. In fact, the museum that displayed it featured a presentation on disability art, and I attended. While I wandered the galleries, I was treated with suspicion and shooed away from “delicate” exhibits–once again, as though I was going to damage something. The staff literally did not recognize me as the performance artist displayed on a large screen on the wall because they couldn’t conceive a disabled body being art. In this space, my body was dangerous, clumsy, and unwelcome.

And in fact, despite it being a busy night at the gallery, with crowds wandering the exhibit, this is what the room in which the disability lecture took place looked like:

Ableds who insisted on a more “painterly” or “abstract” version of my piece also fundamentally miss the critique against the art world.

There is a tendency in performance art for extremism about how far to push the body or what a body should be able to do in performance. I wanted to challenge that idea by pushing my disabled body to limits that, to an able-bodied person, wouldn’t seem extreme at all. I wanted to challenge assumptions about body-based art and what “stress” in relationship to the built environment can mean.

Notice the extreme hyperextension of Dennis Oppenheim’s spine? He gets institutional applause while disabled bodies are erased.

This is also why, for the Parallel Stress series, I have my husband and sometimes-caregiver take the photos under my direction. Abled caretakers, parents, and significant others are almost always believed over disabled & chronically ill people. They also tend to exploit images of us for pity. Having my husband document the performances is an invitation for viewers to consider issues such as consent, credibility, and the subversion of roles: By directing the image, I am testing viewers in a sense. What and who do they believe?

They believe Dennis Oppenheim about his extreme body stress. Do they believe me? Do they understand the trust and consent required to put me into a painful pose that dislocates my joints, challenges my balance, and exposes my vulnerability in the cityscape?

Consent is always an issue where disabled bodies are represented. Abled people often post our images on social media for inspiration porn memes, feel-good pats on the back if they “helped” us with a task, to make fun of our appearance, or to question our disabilities.

Lewis Hine took his investigative photos without informed consent of his subjects. Subterfuge may have been necessary for the investigative nature of his work, but ethically questionable given the private medical, social, and personally identifiable information attached to the images, sometimes even 1st and last name. According to the National Archives:

To obtain captions for his pictures, he interviewed the children on some pretext and then scribbled his notes with his hand hidden inside his pocket. Because he used subterfuge to take his photographs, he believed that he had to be “double-sure that my photo data was 100% pure–no retouching or fakery of any kind.” Hine defined a good photograph as “a reproduction of impressions made upon the photographer which he desires to repeat to others.” Because he realized his photographs were subjective, he described his work as “photo-interpretation.”

Oppenheim, in repurposing these pictures, has once again subjected these children & adolescent bodies–poor, disabled, marginalized–to publication without permission. That they are dead does not erase this ethical problem, and it is possible they have descendants. Hines, of course, had noble motivations of social justice, to stop child labor.

But what are Oppenheim’s intentions?

“These are actually very sexy images of teenage girls. I found that so odd,” She told Vice, when asked what drew her to the images. “They’re classically posed and sexualized images of the backs of girls; there’s no eye contact, no gaze to return. There’s something about them that’s voyeuristic.”

Again, as an abled artist, she is unaware of sensitive disability issues, including the fetishization of disabled bodies. It’s not that these bodies lack sensuality or beauty, but rather, Oppenheim lacks a context for how she views them and uses them. She points to one boy child laborer being dressed in a separate photo as evidence the girls were sexualized (Gat), which is a valid criticism; however, she feels any sensuality she perceives in these “voyeuristic” photos of textile workers translates to ownership–literal ownership, as the titles of Hine’s photos become the titles for her reprints. (Notice, BTW, how the Vice article never probes Oppenheim about disability identity and disability art; curators, art institutions, and art writers prefer not to see disability as an identity.)

She is the one who has wandered into these images as a voyeur: Her stated intention is to rescue these workers’ humanity by presenting their sensuality, and yet, her critique of the original photos is that they already are (in her view) sensual. Never mind the paper covering the workers’ breasts–to me, reminiscent of a medical setting, an attempt to preserve modesty during an examination. What she seems to mean is these bodies must be sensual in a very particular way–through the marking of her abled gaze.

In general, Oppenheim’s work questions the documentary nature of photography, as well as explore trans-digital modes of creation. To upend notions of “archives” and the inherent distance between subject and viewer, she has inserted vertical white lines into Hines’ photographs, alongside the curved spines of the photographic subjects. This is not about justice for disabled bodies; it is about using them as metaphors.

I am tired of abled people using my spine as a metaphor:

Disability art, by contrast to art about disability, makes a statement about our identities. No longer are we mere metaphors for abled people’s struggles. As Jennifer Eisenhauer writes:

The conceptual understanding of artists in the Disability Arts Movement marks a significant shift: from prior discourses of disability. Within the Disability Arts Movement a critical distinction is made between disabled people doing art and disability artists (Barnes & Mercer, 2001). The inclusion of disabled people doing art m art curriculum places an emphasis upon the representation of difference through a curriculum of admiration and appreciation in which individual artists are admired for their ability to create work similar to other able-bodied artists. In contrast, the discourse of the disability artist engages in a critical process of questioning the sociopolitical construction of disability and related ableist ideologies. Such work can include the expression of admiration and appreciation inherent to the construct of disabled people doing art while also introducing critical questions about the formation, maintenance, and possible disruption of ableist ideologies. (9)

The sensuality abled viewers of my Parallel Stress craved wiped out the fundamental issue presented in the piece: that my stress as a disabled body was due to the built environment. I was locating my disabilities outside of my body, outside of my spinal cord, into the world over which abled people have long designed for themselves at the exclusion of disabled bodies.

Abled viewers might enjoy work about disability, but they resist disability art.

Abtracting and sensualizing my work also erases the trauma associated with it: My skirt is printed with my oldest brother’s police booking photo because the traumas he inflicted on me cannot be separated from the traumas experienced through and because of my disabilities–and some of my disabilities (PTSD, anxiety) are a direct result of his abuse. This erasure of mental illness as a driver of my aesthetics is not unintentional, but rather, the entire point: “Traditionally,” writes Tobin Siebers (69), “we understand that art originates in genius, but genius is really at a minimum only the name for an intelligence large enough to plan and execute works of art—an intelligence that usually goes by the name of ‘intention.’ Defective or impaired intelligence cannot make art according to this rule. Mental disability represents an absolute rupture with the work of art. It marks the constitutive moment of abolition, according to Michel Foucault, that dissolves the essence of what art is.”

The color of my suitcase–a statement on the baggage of gender, as I am nonbinary: erased by the Prisma filter.

Every aspect of that piece, from the red wig made of plastics and therefore petrochemicals (representing my brother’s Pontiac GTO) to the way I held the cane -in the wrong hand, to create a balance challenge and to highlight my cane in the foreground as a kind of prosthetic backbone- was erased by the Prisma filter.

Realism was also essential to my piece because I was calling out the City of Lafayette for its ableist city planning. It worked. The protest worked. The city identified the location and paved that particular sidewalk:

Had I promoted it as a sensual Prisma filtered piece, they never could have identified it.

Likewise, people who worked in the mills and factories and experienced scoliosis, knock knees, and even loss of bone marrow from it do not describe that trauma in “sensual” terms. William Dodd, a self-proclaimed “factory cripple,” wrote of how the marrow of his bones dried up due to poor circulation from bone deformities. “The bones then decay, as in my arm; amputation is resorted to, or life lost.” This is a far cry from fetishistic voyeurism.

It’s not, of course, that disabled bodies aren’t sensual; it is simply not for abled people to define. When abled people do so, they tend to erase the realities of disability. Oppenheim seems to believe disabled bodies can only be humanized absent of their traumas.

Dodd also struggled to find a romantic partner and to integrate into society:

The pain, the internalized ableism, the rejection: Oppenheim does not know this element of the story.

That abled gaze, staring in horror of our bodies, inspires rebellion in disability art.

Many disabled artists challenge the abled gaze by “staring back.” Eisenhauer writes of artist Carrie Sandahl:

Performance artist Carrie Sandahl presents her body as a consumed and inscribed text in the art-life piece titled The Reciprocal Gaze (Sandahl, 1999, p. 25). In this performance, Sandahl walks outside while wearing a lab coat and white pants completely covered in red text as well as drawings of a spinal cord and hipbones (Thomson, 2005). As she encounters people’s stares, she hands them a piece of paper that details her medical history. The text on her clothing includes common comments and questions that she experiences in her everyday life, such as, Are you contagious? I bet the Easter Seals could help you. Do you ever dream that you’re normal? Along with these questions, she includes drawings of her scars drawn to size and in the exact location of the scars on her body. Adjacent to the scars, are the names of the doctors that performed the surgeries. As she describes it, “the doctors who that scar belong to” (Mitchell & Snyder, 1997). In her pelvic region, she includes the statement that she can have sex and bear children. In addition, throughout the collage of text and drawing, Sandahl includes references to psychoanalytic theory in regards to how we define ourselves through the Other. (13)

When my disabilities became visible, my first instinct was to design and print fabrics with my medical images. I call this one my Syringomyelia Skirt, and every time I get new images, I design and print more panels, expanding the skirt into something unwieldy. The process of seam ripping fabrics mimics surgery; sewing mimics stitches.

I did not yet know I fit into a tradition such as that of Carrie Sandahl, but once I learned of it, I realized the importance of this discourse, of refusing the abled gaze (Fig. 7).

I also became interested in imposing a “standard” backbone over mine — not to explore the sensuality of my scoliosis, but to “stare back” at the abled gaze, as in this image, which is not on its own a complete piece, but part of a performance (Fig. 8):

I use the background of my home and the cold blue light to suggest the condition of being “homebound,” which to the outside world equates to a kind of death. It mimics the eerie lighting of a morgue. Notice the backbone model, when placed upon my back, curves naturally along with it? This is defiance to models and straight lines such as Oppenheim draws over subjects.

And yet, my body is ambiguous here. It can be inferred that my disability has to do with my back or spinal cord, but you cannot see it. I hold the model backbone over mine in such a way that my arms arms are hidden; this was done to disguise the remote for the camera, as well as the metal handle for the backbone. It hadn’t occurred to me to see it as an image of amputation until someone on social media asked whether I Photoshopped my arms out on purpose.

The question intrigues me: Was my pose or how people saw my pose an unconscious internalization of all those famous sculptures with “amputated” (actually, lost to damage) limbs?

Tobin Siebers points to Magritte’s Venus as an example of the way disability renews art and becomes part of its beauty. For the original Venus de Milo, missing arms reflected damage over time; for Magritte, it was the defining characteristic and what made it beautiful (65). With blood painted on her stumps, Venus becomes a representation of disability (Fig. 9).

The statue is entitled “Les Menottes de Cuivre,” which translates to “The Copper Handcuffs.” The metal copper is ruled by Venus, so it makes sense, but “handcuffs” feels … strange here, given the missing hands. In a sense, Venus is here handcuffed to herself, to this representation. Or perhaps it’s a statement on her disability, her amputation. In any case, it isn’t own voices disability art, but it is a kind of disability poetics, albeit exploited for surrealist aims–perhaps to generate horror by answering the question ableds so often ask: “What happened?”

Own voices is key: abled people do not understand disabled bodies or disabled lives and the complex interrelationship between disabled bodies and work. Does Lisa Oppenheim know, for example, that it’s legal in the United States to pay disabled people less than the minimum wage in sheltered workshops? She never makes these connections in the exhibit, which seems rather to present these curved backs as nothing more than the lines and curves of the textile weaves they produced. It all seems far in the distant past, rather than a pressing issue today.

I could tell her stories about my own work history. Detasseling corn with bloody hands and dislocating joints in the muddy corn fields in 100-degree+ heat in Iowa summer at age 13; folding hot laundry in the basement of a hotel because they didn’t want an epileptic in the front area where someone might get scared by a seizure, and how that hot work caused more seizures and caused me joint problems from the long hours standing & stooping & lifting heavy loads with Ehlers Danlos Syndrome; how many jobs I have lost seeking accommodations for my non-standard body and needs; how I didn’t get to do my PHD in art because it wasn’t accessible.

As for me, when I rolled my rollator into the Lisa Oppenheim: Spine exhibit, I could not hold back tears. “I wish one of my disabled friends were here,” I told my husband. “I need someone here with me who understands, who can feel this exhibit in their backbone.”

Works Cited

“Lisa Oppenheim: Spine.” MOCA Cleveland, n.d. http://www.mocacleveland.org/exhibitions/lisa-oppenheim-spine

“Teaching with Documents: Photographs of Lewis Hines and Documentation of Child Labor.” National Archives, 21 February 2017.

https://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/hine-photos

Dodd, William. A Narrative of the Experience and Sufferings of William Dodd a Factory Cripple. London, L. & G. Seeley, 1841.

Eisenhauer, Jennifer. “Just Looking and Staring Back: Challenging Ableism Through Disability Performance Art.” Studies in Art Education A Journal of Issues and Research, vol. 49, no.

1, 2007, pp. 7-22.

Gat, Orit. Lisa Oppenheim Unravels Haunting Images of Teenage Textile Workers. Vice. 15 September 2017.

Hine, Lewis. Mildred Benjamin, 17 years old. Right dorsal curvature. Scoliosis. Right shoulder higher than left. Shows incorrect position required to perform this kind of work. 1917,

Magritte, Rene. Les Menottes de Cuivre. 1931, patinated bronze.

Oppenheim, Lisa. Incorrect sitting position for postural deformity and dorsal curvature cases. Scoliosis. Stooping, lopsided or humped over position. Work in this position is harmful.

2017, dye sublimation print on aluminum, Tanya Bonakder Gallery, New York/Los Angeles.

Oppenheim, Lisa. Mildred Benjamin, 17 years old. Right dorsal curvature. Scoliosis. Right shoulder higher than left. Shows incorrect position required to perform this kind of work.

2016, dye sublimation print on aluminum, Tanya Bonakder Gallery, New York/Los Angeles.

Oppenheim, Lisa. Jacquard Weave (Apple Blossoms). 2017, Jacquard woven cotton, mohair and linen textile in wood, Tanya Bonakder Gallery, New York/Los Angeles.

Siebers, Tobin. “Disability Aesthetics.” Journal for Cultural and Religious Theory, vol. 7 no. 2, 2006, pp. 63-73.